From the broadest of international perspectives, cultural heritage institutions have been slow to adapt to the introduction and proliferation of professional and amateur digital photography, and to embrace freely available digital access to their collections. This is largely due to the shifting nature of trends in scholarship, the way that research is now conducted in a reading room environment and a librarian or archivist’s inherent instinct to retain control of the collections within our care. Many of the students and researchers who are the most frequent patrons in our reading rooms have shifted away from the study of single items or limited data-sets which was so popular in the mid-twentieth century (e.g. an edition of a seventeenth century poem, a single manuscript copy of a medieval text). They have instead turned to methods of enquiry which require vast amounts of data on the creation, production, and use of texts or works of art.

A researcher coming in for their first visit to a reading room may wish to call up a dozen items or more in one day in order to photograph everything they see and take quick notes on the physicality of those items. They may then wish to return to their office in order to read the books or manuscripts documented, conduct methodological research and take time to think critically. The development of this “humanities field work” method of research is due in part to the continual lack of funding for research trips. Much of it, however, is due to the democratization of the ability to capture and reproduce quickly images of what one sees in a controlled reading room environment. Self-service photography, or casual/DIY digitization, has become a fact of life in the reading room in the past six to eight years as high-quality digital cameras have become increasingly available and accessible. Any researcher who makes extensive use of primary materials found in libraries, archives and museums now has in their toolkit a device, be it a digital camera, tablet or phone, which they can use to take digital images that can be rapidly consulted.

This development offers libraries and archives the opportunity to provide quick, low-cost and high-quality reproductions of a book or manuscript, or to allow researchers to take their own photographs. Instead, many libraries and archives have put up barriers in order to stem the flow of freely accessible reproductions of content within their care. This has largely involved the practice of charging prohibitive fees for licensing images for reproduction and in-house photography or by not allowing photography in their reading rooms. There have certainly been major exceptions to this trend. The USA’s rulings on charging licence fees for items in the public domain, a privilege only afforded to copyright holders, have provided clear guidance there. [1] Nevertheless, the wide international variance in how much a researcher has to pay to use a reproduction in a publication, if they are even allowed to bring a camera into the reading room in the first place, speaks volumes as to how fragmented the cultural heritage sector is on this topic.

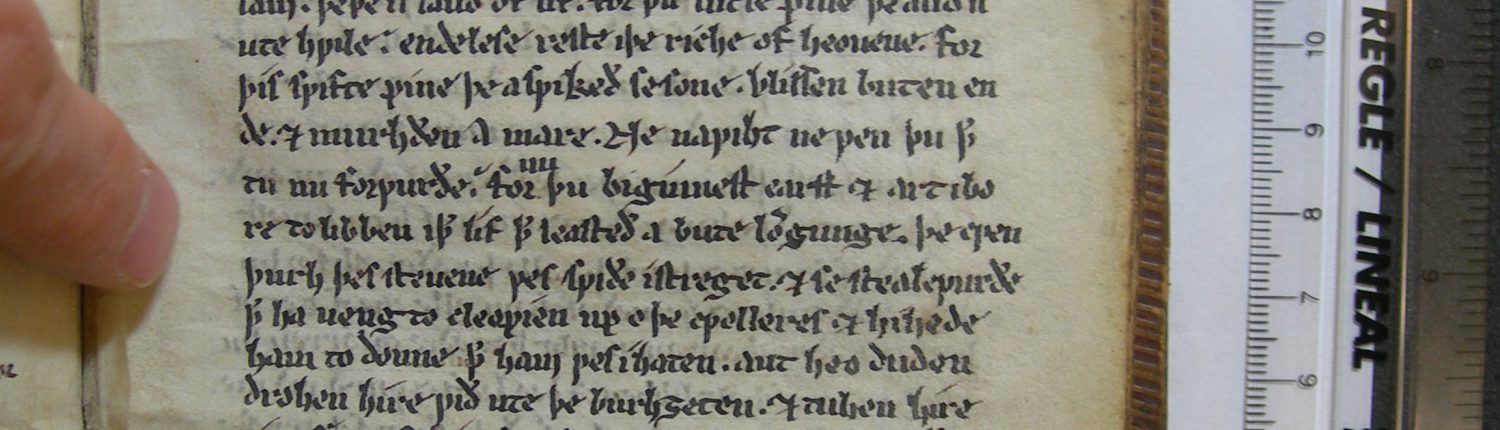

This disparity in what libraries or archives allow or charge can be completely bewildering to a researcher. In the opening salvo of her critique of the imaging policies of libraries and archives, Kate Rudy recounts helping her friend, a scholar of medieval English, source images for an upcoming publication: “Each repository she approached had its own rules, pricing schedule, and regulations concerning permission to reproduce […] By the time her manuscript went to press, she had spent more than €500 for the thirteen images in her book (‘thirteen separate experiences of trauma,’ as she put it), and vowed never to include another illustration in any future book.”[2]

Surveying the landscape of photography policies

In December 2015, I put together an online survey in order to capture a snapshot of what libraries and archives are currently doing in terms of allowing photography in their reading rooms and regulating what can be done with those photographs.[3] This survey, a brief six questions with one free text answer, garnered about 160 responses over the period of one month. The first question was designed to establish the size of the responding library or archive and whether or not they were affiliated with a university, public or private institution. The first topical question on the survey asked if photography was allowed in their reading rooms, allowing for a simple “yes/no” answer. Only eight respondents, about 5%, answered no to this question; even in the past few years, the trend towards more liberal photographic access to collections has slowly become the norm (see Figure 1).

These findings were further corroborated by a survey which I conducted of all special collections held in Russell Group University Libraries, in which only two out of twenty-four did not allow photography.[4] Two of the Russell Group University Libraries charged a daily fee for a reader to use their camera and of the wider, month-long survey exactly the same percentage (8.3%) of respondents said they allowed photography for a fee. Models for fees structures from respondents ranged from $5-£25 per day, and in one case $1 per each photograph taken.[5]

The most alarming variance represented in this survey, however, is what libraries are “allowing” their users to do with photographs which they take in the reading room. At the time of the survey, all but one of the Russell Group libraries imposed some kind of sliding scale of fees for permissions to publish in any form; fees which are separate to the fees levied for the creation of images by the library, such as ordering a scan or photograph. [6] About 85% of the respondents to the month-long survey stated that readers taking their own photographs can use these photographs for “research purposes only” or “must ask permission/pay a fee to use the reader’s photograph in a publication” (see Figure 2). These libraries are essentially claiming rights to images that someone else has taken of items in their collections.

The 15% of survey respondents that did not have these requirements either charged no royalty fees but still required permission to be sought from them before publication (about 9%) or allowed readers to do whatever they liked with their photographs (7%) barring any type of copyright infringement. These numbers are further nuanced by the study that Michelle Light conducted of 125 American special collections libraries’ forms and procedures in regards to permissions and user fees. Light found that:

“[…] approximately 70 percent of special collections require users to seek permission to publish any content from their holdings. This includes seeking permission for public domain content, content that is copyrighted by others, and content with copyrights held by the institution. By contrast, 15 percent of these special collections only require permission to publish when the institution owns the copyright. Fifty-five percent of institutions charge use fees or permission fees, in addition to scanning fees, for publishing any content from their holdings.”[7]

Why do libraries and archives charge permission fees for the publication of images of items in their collections?

The answer to this question is neatly summed up by Light: “We simply follow the practices of our peers.”[8] A more full analysis of where the development of permission fees has grown from can be found in Will Noel’s response in an interview by TED in 2012. He says:

“Libraries containing special collections of medieval materials are normally very careful to write restrictive copyright on their materials. Part of this is historical; that is to say, when images of these manuscripts were published in books, it didn’t have to behave like digital data, and it didn’t have to be free for people to use in all sorts of ways and in different contexts. The images were just reproduced in other books. […] You used to restrict the use of your books to try and make money off reproductions in other books.”[9]

The free-text results from the month-long survey I conducted, and from the survey of Russell Group libraries, show that each library charges a different scale of fees for the rights to publish images of their collections, irrespective of whether the user or the institution has created the images. Some have set fees ranging from £25-£100 per image, some have discounts for students and researchers who are publishing the image in a limited-run academic book; essentially, there is no national or international consensus on what libraries charge users for the rights to publish images.

The real question is why libraries and archives have continued to levy charges for licensing reproductions of items in their care. Most libraries which are affiliated with a larger institution (e.g. college, university, or corporate bodies, local authority archives or public libraries) and certainly libraries which are independent from a higher governing body (national or private libraries) are set income generation targets in order to contribute to an offset income against an annual budget.[10] Late fees, fines for damaged books, printing or copying fees and merchandising are some of the most popular examples of how circulating libraries generate income. Historically, however, licence fees, reproduction fees and merchandising are the only ways that a special collections library or archive can contribute to income generation. Many recent studies and surveys have investigated whether the current model of licence fees in American and Canadian libraries and archives actually generates any profit which can be considered ‘income generation’.[11] All of these surveys have found that when revenue derived from licence fees is factored against the cost of staff time, filing infrastructure and vigilant monitoring of reproduction licence infringement, little to no profit is generated.

In fact, for small- to medium-scale research libraries, the amount of paper work and staff time spent on creating and retaining permissions requests and approvals far exceeds the amount of money that is brought in. Librarians and archivists are in danger of shooting ourselves in both of our feet by scaring away potential use of our collections for publications and by making more work for ourselves without generating any real profit.[12]

This leads me to my second question in this investigation:

Is it legal to charge permission fees for reproductions of items within our care that are in the public domain?

A large percentage of material in most special collection libraries, archives and museum collections is out of copyright, and therefore belongs to the public domain. Librarians, archivists and museum curators are custodians of these items owned by their institutions. The holding institutions cannot claim copyright over items in their possession that are in the public domain and therefore cannot claim copyright over faithful digital reproductions of items in our care that are within the public domain. This was illustrated most poignantly in an international dispute in 2009 when Derrick Coetzee, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote a script that downloaded the image tiles of more than 3000 images from the National Portrait Gallery’s website and re-assembled them into complete, high-resolution images, which he then uploaded to the Wikimedia Commons.[15] The National Portrait Gallery began legal action against Coetzee and Wikimedia as it felt that its copyright over the high-resolution images had been violated.

Grischka Petri’s summary of the National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia dispute illustrates the point of possession and copyright assumption in the cultural heritage sector most succinctly:

“[…] here it was uncontested that Derrick Coetzee had used the images on the NPG’s website. Furthermore, the works of art in question were part of the museum’s collections. Modern copyright has established that it is not the owner of a work of art who is the copyright holder, but the creator: possession does not automatically convey copyright. […] There is no copyright in photographic reproductions of two-dimensional works of art in the public domain. Consequently, under US law, the Bridgeman cases ‘still stand for, at the very least, the important and distinct principle that exact replications of public domain works warrant no copyright protection’ (Dobson 2009: 347). Taking into account recent European and UK case decisions, it is reasonable to state that the same principles are also valid for UK law. […] Metaphorically, Coetzee did not set somebody else’s chicken free; he freed a chicken that did not belong to any specific farmer and should not even be living on a farm in any case. Thus, the time has come to move past the logic of copyright pretensions in regard to reproductions of works of art in the public domain.”[16]

If we follow the rulings of the abovementioned cases and definitions of public domain and copyright, the answer to the question of whether a library or archive can legally charge for the right to publish faithful reproductions of a fourteenth-century papal bull, or a sixteenth-century atlas, or a nineteenth-century triple-decker novel, is clearly “no”.

This is even more true when we consider the rights of an individual photographer who has taken pictures of a book or manuscript in our care that is out of copyright and therefore in the public domain. The photographer (who could be a reader, researcher, a member of the general public viewing an exhibition, etc.) is the creator of the photograph. If that photograph is a simple technical reproduction of the subject, then UK, European and American copyright law states that it is simply a reproduction of a public domain work which has no copyright. If their photograph has elements of artistry or creativity, then the rights belong to the photographer and not the institution that owns the book or manuscript.

It follows that the only way that a library, archive or museum can prevent the reproduction of an item in the public domain in their care from being used in any type of publication or merchandise is by not allowing any form self-service photography in their reading rooms or exhibition galleries. This also applies to faithful reproductions of public domain items in collections created by the host institution. A library or archive can charge for the process of creating a photographic reproduction, for the delivery of any files and for the staff time spent managing the transaction, all of which should be as transparent as possible to the general public. It cannot, however, charge for a licence to publish that reproduction in any format. In fact, once a library or archive hands over that faithful reproduction to an individual, they are free to do whatever they like with that image. This includes using it in a publication or hosting it in full resolution online to illustrate a blog post, or creating new and original artwork with that image, or printing merchandise.[17] As librarians and curators, we can always ask that proper citations be given if the images will be used in publications, but we should be doing that anyway.

When a library, museum, or archive licenses images to a for-profit aggregator like Bridgeman Art Library or Getty Images it does not mean that they are handing over copyright to these agencies. It means that these agencies can add images of a book or manuscript or work of art to their database and charge their users, largely media companies and publishers, a fee for the image because they are providing a value-added service (i.e. the ability to find an image of an “English medieval manuscript” or “woodcut of Christ on the cross” in one database and not have to pay someone to do the image acquisition for them). The profit that is derived for cultural heritage institutions from these for-profit aggregators is not from fees for copyright licences but from subscription fees to these databases. Furthermore, as Michelle Light highlights, these partnerships with commercial companies can be very profitable for both parties.[18]

Learning to let go

For too long, access to items in the care of libraries and archives has been limited by the physical needs and demands of a pre-digital world. It is time we embrace the idea that the whole point of a library is to provide access—in whatever format—to the world’s knowledge, not to keep it behind closed doors. Indeed, as Light states: “If you are part of an institution committed to the advancement of knowledge through teaching and research, then making public domain material freely available is consistent with this mission to disseminate knowledge, encourage appreciation of our cultural heritage, and inspire creativity.”[19]

The inconsistency in permissions to take and reproduce photographs of the unique items in our care is widely recognized by librarians and archivists as one of the major barriers to furthering academic investigation into our collections.[20] An academic researcher’s perspective, however, is perhaps the most pointed with which to close. In her international comparative and personal study of three research libraries and their policies on capture and use of reproductions of items, Rudy describes her experience at Trinity College Dublin in the worst of lights: she was not allowed to take her own photographs of medieval manuscripts in the reading room and the cost of ordering images and obtaining permission to publish them in a scholarly, peer-reviewed journal were extremely prohibitive.[21] The impact on her and others’ scholarship on items held by Trinity College Dublin is acute:

“As a result of Trinity’s policies, scholars routinely avoid using resources housed in this library because of the library’s overly restrictive […] rules and policies […] The numerous problems with access at Trinity College Dublin might explain why the items in their collections are little known and underutilized […] I am able to write about the manuscripts of which I have images, to contextualize them, and ultimately to contribute to the mission of the holding institutions—to preserve, document, and study their own collections—with much greater ease for manuscripts from which I have high-quality images.”[22]

As curators, we have responsibilities to both the material in our care and the people wishing to consult and use it. One of the main hesitations in allowing free-for-all photography in our reading rooms has been conservation needs which are implicit in managing, issuing, and consulting historic items. Most libraries and archives have their own “treasure” items which are regularly wheeled out for talks and public engagement. These items often get called up in a reading room by researchers. If an item is being called up just so it can be photographed quickly and unprofessionally by a reader, would it not make more sense for an institution to increase the amount of high-quality digitization that it makes freely available and keep a similarly available register of what has been photographed by other users in order to avoid duplication? The model employed by the Oxford DIY Digitization project has provided a tantalizing first step towards a crowd-sourced database of images taken in a library and could be one of the many ways that libraries, archives and museums address this issue.[23]

Librarians, curators and archivists play a crucial role in the firmament that supports new and original research; our role is to act as a live conduit between the items in our care and the readers seeking them out. The policies that we enact in our institutions directly affect the nature and direction of research. It is clear that the policies that many of us have adopted or perpetuated in regards to self-service photography and image rights obstruct that process and in many cases could be a breach of public domain and copyright law. We should instead focus on facilitating and fostering curiosity and new lines of enquiry into the collections in our care. In doing so, we can open the doors to our physical and virtual vaults to a new generation of researchers.

References

Astle, Peter J., and Adrienne Muir, ‘Digitization and Preservation in Public Libraries and Archives’, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 34. 2 (2002), 67-79; available at http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/1159209117Dig.%20%26%20pres.%20libs.%20%26%20archs.%202002.pdf [last accessed 12/062016].

Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1999); available at http://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/36_FSupp2d_191.htm [last accessed 11/06/2016].

Dryden, Jean, ‘Copyfraud or legitimate concerns? Controlling uses of online archival holdings’, The American Archivist, 74 (2011), 522-43; available at http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.74.2.d5g2700q5612l4w7 [last accessed 12/06/2016].

Erickson, Kris, et al., Copyright and the Value of the Public Domain: An empirical assessment (London: The Intellectual Property Office, 2015); available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/415014/Copyright_and_the_value_of_the_public_domain.pdf [last accessed 12/07/2016].

Intellectual Property Office, Copyright Notice: digital images, photographs and the internet, Copyright Notice Number: 1/2014, updated: November 2015; available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/481194/c-notice-201401.pdf [last accessed 12/06/2016].

Kapsalis, Effie, ‘The impact of open access on galleries, libraries, museums, & archives’, Smithsonian Emerging Leaders Development Program (April 27, 2016); available at http://siarchives.si.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/2016_03_10_OpenCollections_Public.pdf [last accessed 10/07/2016].

Light, Michelle, ‘Controlling good or promoting the public good: choices for special collections in the marketplace’, RBM: a journal of rare books, manuscripts and cultural heritage, 16.1 (2015), 48-63; available at http://rbm.acrl.org/content/16/1/48.full.pdf+html [last accessed 12/06/2016].

Noel, William, ‘The wide open future of the art museum: Q&A with William Noel’, TEDBlog (29 May 2012); available at http://blog.ted.com/the-wide-open-future-of-the-art-museum-qa-with-william-noel/ [last accessed 11/072016].

Pautz, Hartwig, and Adam Poulter, ‘Public libraries in the “age of austerity”: income generation and public library ethos’, Library and Information Research, 38.117 (2014), 20-36; available at http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir/article/viewFile/609/629 [last accessed on 12/07/2016].

Petri, Grischka, ‘The Public Domain vs. the Museum: The Limits of Copyright and Reproductions of Two-dimensional Works of Art’ Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 12.1 (2014), art. 8; available at http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021217 [last accessed 12/06/2016].

Rudy, Kathryn M., ‘Open Access: Imaging Policies for Medieval Manuscripts in Three University Libraries Compared’, Visual Resources: an international journal on images and their uses, 27:4 (2011), 345-59; available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2011.621870 [last accessed 12/06/2016].

The National Archives, Copyright and related rights (Crown copyright, 2013); available at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/copyright-related-rights.pdf [last accessed 15/07/2016].

| 2. Do you allow self-photography/digitization in your reading room? (i.e. do you allow readers/patrons to take their own photos or do their own scanning?) | |||

| Answer Options | Response Percent | Response Count | |

| Yes | 95.1% | 154 | |

| No | 4.9% | 8 | |

| answered question | 162 | ||

| skipped question | 10 | ||

| 3. If you answered ‘yes’, do you charge readers to take their own photographs/scans? | |||

| Answer Options | Response Percent | Response Count | |

| Yes | 8.3% | 13 | |

| No | 91.7% | 143 | |

| answered question | 156 | ||

| skipped question | 16 | ||

Figure 1 Results from questions 2 and 3 from a survey conducted 11 December 2015-11 January 2016.

| 5. If you allow photography/digitization in the reading room, what licence do you allow for readers to do with their images? | ||

| Answer Options | Response Percent | Response Count |

| Research purposes only | 64.8% | 92 |

| Rights managed (restrictions on usage, must ask permission and/or pay to use in any type of publication) | 18.3% | 26 |

| Royalty-free (no charge for use in publications, must ask permission to use) | 7.7% | 11 |

| Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY (or something similar) | 9.2% | 13 |

| answered question | 142 | |

| skipped question | 30 | |

Figure 2 Results from question 5 from a survey conducted 11 December 2015-11 January 2016.

[1] The United States District Court ruled in the case of Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1999) that “exact photographic copies of public domain works of art would not be copyrightable under United States law because they are not original” and therefore a library or archive cannot claim licence of exact photographic reproductions of public domain material in their collection. Available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/36_FSupp2d_191.htm [last accessed 11/06/2016].

[2] Kathryn M. Rudy, ‘Open Access: Imaging Policies for Medieval Manuscripts in Three University Libraries Compared’, Visual Resources: an international journal on images and their uses, 27.4 (2011), 345-59 (pp. 345-46); available http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2011.621870 [last accessed 12/06/16].

[3] Available at https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/PWCHBSK, open from 11 December 2015-11 January 2016 [last accessed 11/o1/16].

[4] The Russell Group “represents 24 leading UK universities which are committed to maintaining the very best research, an outstanding teaching and learning experience and unrivalled links with business and the public sector”, a full list of members can be accessed here: http://russellgroup.ac.uk/about/our-universities/ [last accessed 11/06/2016]. The institutions not allowing photography in the reading room at the time of this survey (6 January 2016) were the University of Southampton and Imperial College London.

[5] At the time of this survey, both of the Special Collections Libraries of the University of York and the University of Nottingham charged £10 per day for a reader to use their own camera in the reading room.

[6] The London School of Economics Library states on their website that “There are no restrictions on copying and publishing works that are out of copyright … We place no restrictions on the quality of images taken, and we do not charge a fee for using a camera.” Available at http://www.lse.ac.uk/library/usingTheLibrary/accessingMaterials/readingRoomAccess/Copying-information.aspx [last accessed 11/06/2016].

[7] Michelle Light, ‘Controlling goods or promoting the public good: choices for special collections in the marketplace’, RBM: a journal of rare books, manuscripts and cultural heritage, 16.1 (2015), 48-63 (p. 50); available at http://rbm.acrl.org/content/16/1/48.full.pdf+html [last accessed 12/06/2016].

[8] Light, ‘Controlling goods’, p. 49.

[9] William Noel, ‘The wide open future of the art museum: Q&A with William Noel’, TEDBlog (29 May 2012): http://blog.ted.com/the-wide-open-future-of-the-art-museum-qa-with-william-noel/ [last accessed 11/06/2016].

[10] For a recent survey and analysis of income generation practices in UK public libraries, see Hartwig Pautz and Adam Poulter, ‘Public libraries in the “age of austerity”: income generation and public library ethos’, Library and Information Research, 38.117 (2014), 20-36; available at http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir/article/viewFile/609/629 [last accessed 12/06/2016].

[11] See Peter J. Astle and Adrienne Muir, ‘Digitization and Preservation in Public Libraries and Archives’, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 34.2 (2002), 67-79; available at http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/1159209117Dig.%20%26%20pres.%20libs.%20%26%20archs.%202002.pdf [last accessed 12/06/2016]; Jean Dryden, ‘Copyfraud or legitimate concerns? Controlling uses of online archival holdings’, The American Archivist, 74 (2011) 522-43; available at http://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.74.2.d5g2700q5612l4w7 [last accessed 12/06/2016]; and Light, ‘Controlling goods’.

[12] See the conclusion of Effie Kapsalis, ‘The impact of open access on galleries, libraries, museums, & archives’, Smithsonian Emerging Leaders Development Program (April 27, 2016); available at http://siarchives.si.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/2016_03_10_OpenCollections_Public.pdf [last accessed 10/07/2016], which states: “With an open access policy, revenue from rights and reproduction activities are reduced, but retaining more restrictive terms of use may cost organizations in funding opportunities, staff time, and reputation.”

[13] For a working definition of “public domain” in the UK, see Kris Erickson, et al., Copyright and the Value of the Public Domain: An empirical assessment (London: The Intellectual Property Office, 2015); available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/415014/Copyright_and_the_value_of_the_public_domain.pdf [last accessed 12/06/2016]:

- Copyright works which are out of term of protection (Literary and artistic works created by authors who died prior to 1944);

- Materials that were never protected by copyright (Works from antiquity and folklore);

- Underlying ideas not being substantial expression (Inspiration taken from pre-existing work that may include genre, plot or ideas);

- Works offered to the public domain by their creator (Certain free and open licensed works without restrictions).

Copyright and archival collections in the UK, however, have many grey areas that their caretakers and researchers should be aware of. A guidance document issued by The National Archives in 2013 (Copyright and related rights; available at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/copyright-related-rights.pdf [last accessed 15/06/2016]) states that “literary, dramatic and musical works that were still unpublished when the current statute, the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, came into force in 1989 will be in copyright until 2039 at the earliest – this is especially important in archives, where most material is classified as unpublished.” However, manuscripts from the medieval and early modern periods which were produced before the modern notion of copyright was instituted would qualify as “works from antiquity and folklore” and therefore should fall within the parameters of UK public domain.

[14] For the United Kingdom, see Intellectual Property Office, Copyright Notice: digital images, photographs and the internet, Copyright Notice Number 1/2014; updated November 2015; available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/481194/c-notice-201401.pdf [last accessed 12/06/2016], which states:

“Simply creating a copy of an image won’t result in a new copyright in the new item. However, there is a degree of uncertainty regarding whether copyright can exist in digitised copies of older images for which copyright has expired. Some people argue that a new copyright may arise in such copies if specialist skills have been used to optimise detail, and/or the original image has been touched up to remove blemishes, stains or creases. However, according to the Court of Justice of the European Union which has effect in UK law, copyright can only subsist in subject matter that is original in the sense that it is the author’s own ‘intellectual creation’. Given this criteria, it seems unlikely that what is merely a retouched, digitised image of an older work can be considered as ‘original’. This is because there will generally be minimal scope for a creator to exercise free and creative choices if their aim is simply to make a faithful reproduction of an existing work.”

For the United States, see Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1999): https://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/36_FSupp2d_191.htm [last accessed 11 June 2016].

[15] For a complete summary of this dispute, see ‘National Portrait Gallery and Wikimedia Foundation copyright dispute’; available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Portrait_Gallery_and_Wikimedia_Foundation_copyright_dispute [last accessed 12/06/2016].

[16] Grischka Petri, ‘The Public Domain vs. the Museum: The Limits of Copyright and Reproductions of Two-Dimensional Works of Art’, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 12.1 (2014), art. 8; available at http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021217 [last accessed 12/06/2016].

[17] Petri, ‘The public domain vs. the museum’, provides a poetic example of how libraries and archives could consider operating their reprographic services and digital repositories: “If the image of an object in the British Museum’s collections has not yet been photographed, a reasonable fee of £60 is incurred. In this way, the first-time user becomes the sponsor of a reproduction, since it will be included in the digital collection and become freely available.”

[18] Light, ‘Controlling goods’, p. 57.

[19] Light, ‘Controlling goods’, p. 54.

[20] Light, ‘Controlling goods’; Noel, ‘The wide open future of the art museum’.

[21] Rudy, ‘Open Access’, pp. 351-53, states that at the time of writing “The cost of new photography [at Trinity College Dublin] is €20 to set up the manuscript, and then €1.50 per shot from the same manuscript. The cost for existing photography (including scanning existing slides or sending existing digital images) is the same: €20 to process the order, and then €1.50 per image… To obtain permission to publish the resulting images in an academic book or article, a scholar must pay €90 per image (world rights/one language).”

[22] Rudy, ‘Open Access’, pp. 355-57. The University of Leiden Library and the Beinecke Library at Yale University were Rudy’s other test libraries where she found that self-service photography or ordering images was conducted with “with a minimum of red tape.”

[23] ‘Bodleian Special Collections’; available at https://www.flickr.com/groups/bodspecialcollections/ [last accessed 17/06/2016].